How Neighbours Support Reintegration in Aweil: Evidence from a Rapidly Changing Border City

Image for representational purposes only | Photographed by René Habermacher

Ali Juma introduced himself simply: “a disabled refugee from Western Sudan,” someone who had moved more times than he could count in the years since the war in Sudan began. His journey is on a pause, for now, in Aweil, a place he reached after fleeing roadblocks, armed groups, and the loss of contact with his family.

To him, Aweil is a refuge, a place where he can finally “sleep without gunshots.” It is also a city shaped by movement. Located on the borders of Sudan,, refugees from Sudan, returnees from Khartoum, IDPs from South Sudan’s earlier conflicts, and seasonal pastoralists all pass through or settle this capital of Northern Bahr el Ghazal state.

Aweil’s economy runs on daily labour, small trade, and overstretched services. Our research shows that only 4 in 10 displaced households report adequate access to basic services, and refugees are the least likely to earn an income, despite 72.8% of displaced people saying they work in some form. Yet the town remains one of the few places in the region considered safe, and over 78% of residents — hosts and displaced — say they feel secure where they live. It was into this mix of safety and strain that Ali arrived, hoping to rebuild a life.

Finding A Community

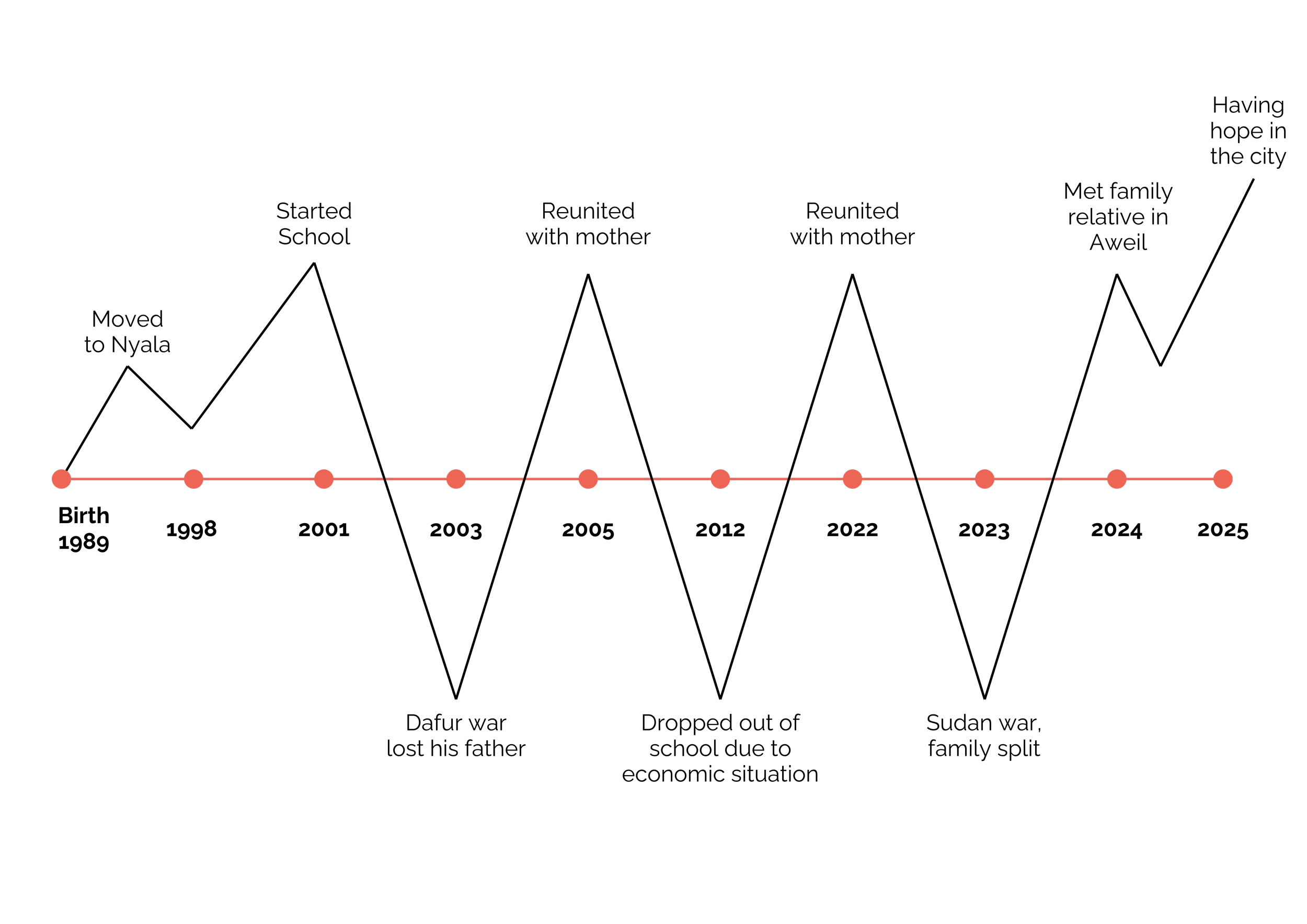

Ali was born in 1989 in Beliel, South Darfur. His childhood was marked by continuous displacement, first when his family relocated to Nyala for safety and later by the conflict that repeatedly disrupted their lives. In 2023, when the war finally reached his neighbourhood, Ali fled south with crowds of others, passing checkpoints where, as he recalled, “if you refused to hand over anything, they could even kill you.” Weeks later, he crossed into Aweil — tired, separated from his family, but relieved to have reached a place people said was safe.

When Ali crossed into South Sudan in August 2023, he did so with a group of people he had met along the way — strangers bound together by the same need for safety. They moved from town to town until organisations at the border escorted them onward to Aweil. According to OCHA, nearly 9000 refugees entered Aweil from Sudan in 2023. He remembers arriving tired but relieved, and being met first not by officials but by other Sudanese who had settled in the city earlier.

They welcomed him with food, clothes, and words of comfort, easing the shock of reaching a place he had never imagined would become home. Local chiefs followed soon after, offering greetings and reassurance. “These people are friendly,” he said

In the months that followed, Ali began settling into Aweil’s daily rhythm. The city’s calm stood in contrast to what he had fled, and like the 78% of displaced and host residents who report feeling safe, he found a measure of peace in its relative stability.

The Strains and Strengths

With only 4 in 10 displaced households reporting adequate access to basic services, he soon learned that safety did not guarantee ease. Housing was crowded, work was informal, and services were overstretched. Ali chose to focus on what he had rather than what was missing. “The little services that I’m getting now is better than remaining in Sudan and dying for nothing,” he said, noting that he feels protected by the local authorities.

His daily life revolves around the main market, where friends from his community invited him to stay with them and assist in their shops. His disability limits the kinds of jobs he can take on, but he works whenever he can, selling goods for shop owners when they step away. Others he knows have managed to establish small businesses with help from relatives, but he has not joined savings groups or cooperatives — “I have nothing at all,” he says and without capital, his hopes of starting a business of his own remain out of reach.

In Aweil, Ali’s sense of stability has come from the networks around him. He spoke of NGOs — “the UN, Red Cross and many others” — whose presence reassured him that services, even if limited, would not disappear overnight. Local authorities also featured strongly in his reflections. He says, “the government here… protects citizens including us refugees very well.”

This trust aligns with wider patterns in Aweil, where our research shows that over 90% of residents — hosts and displaced — report high trust in NGOs and the UN, and nearly 70% express trust in local government structures. Yet psychosocial pressures remain widespread in the city; 42% of displaced people report frequent sadness and 27% stress, shaped by economic strain, and separation from family, feelings Ali echoed when he said that ‘thoughts of his wife and mother make me feel bad” even on better days.

Independence, Inclusion, and What Comes Next

Like many displaced people in Aweil, where only 28% take part in community meetings compared to 56% of hosts, he relies on refugee leaders to attend gatherings, while most forums focus on awareness rather than influence. He notes that organisations “give opportunity to raise our concerns when we are in the settlement camp,” even if these exchanges rarely extend into town life.

This is precisely where Participatory Forums can shift reintegration outcomes: by creating structured spaces where county actors, chiefs, hosts, refugees, and returnees jointly identify priorities and push for change.

For Ali, who hopes to “be independent and have my own house and business to run,” such forums represent the first meaningful chance to shape the systems he depends on. His outlook mirrors the wider sentiment in Aweil, where 71% of displaced residents remain hopeful about the future despite strained services — a blend of optimism and uncertainty that defines his own desire to rebuild, reconnect with his family, and regain stability in a place he now considers safe.

This story is based on a conversation with Ali and our findings from the study. It reflects her lived experience, edited for clarity, and highlights the integration themes central to LLEARN’s work.